Over the years, I've told colleagues and friends about things I have seen or experienced. Many times, people have said that I should write them down so that they won't be lost and forgotten, since some of them might be useful parts of our history. I've been writing them down, without being sure what I would do with them. I decided to gradually post them on this website, and see what reactions I get. I suggest reading from the bottom up (starting with the August 2017 post "The Meritocracy"). Thoughtful and kind feedback would be useful for me, and would help me to revise the exposition to make it as useful as possible. I hope that while you read my stories you will ask yourself "What can I learn from this?" I'm particularly interested in knowing what you see as the point of the story, or what you take away from it. Please send feedback to asilverb@gmail.com. Thanks for taking the time to read and hopefully reflect on them!

I often run the stories past the people I mention, even when they are anonymized, to get their feedback and give them a chance to correct the record or ask for changes. When they tell me they're happy to be named, I sometimes do so. When I give letters as pseudonyms, there is no correlation between those letters and the names of the real people.

Monday, November 5, 2018

The vent for the men's room

Sunday, October 7, 2018

Outtake #4: Life and Death

Wednesday, October 3, 2018

Outtake #3: Survival

Tuesday, October 2, 2018

Outtake #2: Gender ratio for students at the University of Cambridge and at Churchill College

Monday, September 24, 2018

Outtake #1: When something goes wrong

My next few posts will be "outtakes" from earlier drafts of my September 16, 2018 piece. See especially my commentary under the following outtake.

Sunday, September 16, 2018

Moving beyond affirmative action for men

I joke that all of my higher education was at single sex universities ... but unfortunately for a sex of which I'm not a member. The disparities between the way men and women were treated at those universities ranged from serious to laughable.

Sunday, September 2, 2018

"Alice, what are you doing next year?"

I replied, "I got into MIT, Chicago, and Berkeley. Princeton makes its decisions next week. If I get into Princeton, I'll go there."

Q's face turned beet red. "You mean ... you're going to grad school?! ... In mathematics?!"

"Yes."

Not only had I done well in the courses I took from Q, but I had done well in general (I had already been named one of the few students to get junior year Phi Beta Kappa, and would soon graduate summa cum laude in mathematics). Had I been male, no one would have been surprised that I planned to go to grad school. In mathematics.

Q had clearly been planning to tell me something, but now thought better of it.

I asked, "What were you going to say?"

"Oh, nothing. It doesn't matter." He looked very embarrassed.

Curious, I insisted. "Please. You were going to say something. What was it?"

Hesitatingly, he told me that a math teacher at his son's high school had recently left. Q had thought that I might not have plans for next year, and would be interested in the position.

I deduced from Q's embarrassment that he would not have had this conversation with a comparable male student. But it's nice to know that he realized he should be embarrassed!

Friday, August 24, 2018

Immunizations

I tried to figure it out. After observing him and others, it seemed to me that he believed he was immunizing himself against accusations of sexism. If I charged him with sexism, I'd be implicitly accusing him of lying. He thought I'd be reluctant to do that.

It's not just men who try to immunize themselves. Many people recognize that when someone tells a woman, in a professional setting and in front of her colleagues, how lovely she looks, while praising men for their work, this can undermine her professional stature in the workplace. But some women readily compliment other women on their clothes, in front of their colleagues. Sometimes they accompany it with "This would be sexist if a man said it, but it's fine since I'm a woman." If it's not OK when a man does it, why is it OK when a woman does it? In my book, saying it's OK doesn't immunize their actions from scrutiny.

And when someone begins a sentence with "I know this might sound racist (or sexist), but …", that self-awareness doesn't necessarily make it less racist or sexist.

Saturday, August 18, 2018

In job ads, say what you mean and mean what you say

Every so often I receive an email message or phone call, sometimes from a friend, sometimes from someone I don't know, saying that his or her department has a job, here's what they're looking for, and can I spread the word and help them find someone who fits the bill?

Tuesday, July 31, 2018

postscript to July 25 post

Wednesday, July 25, 2018

A mountain of unwashed coffee cups

I visited a mathematics research institute in Bonn, Germany sometime in the 1990s. In addition to offices, each floor had a small kitchen with ceramic coffee cups, coffee-making equipment, and a prominent sign stating that everyone was responsible for washing their cups after use. So I was surprised to find a mountain of unwashed coffee cups piled in the sink.

Wednesday, July 18, 2018

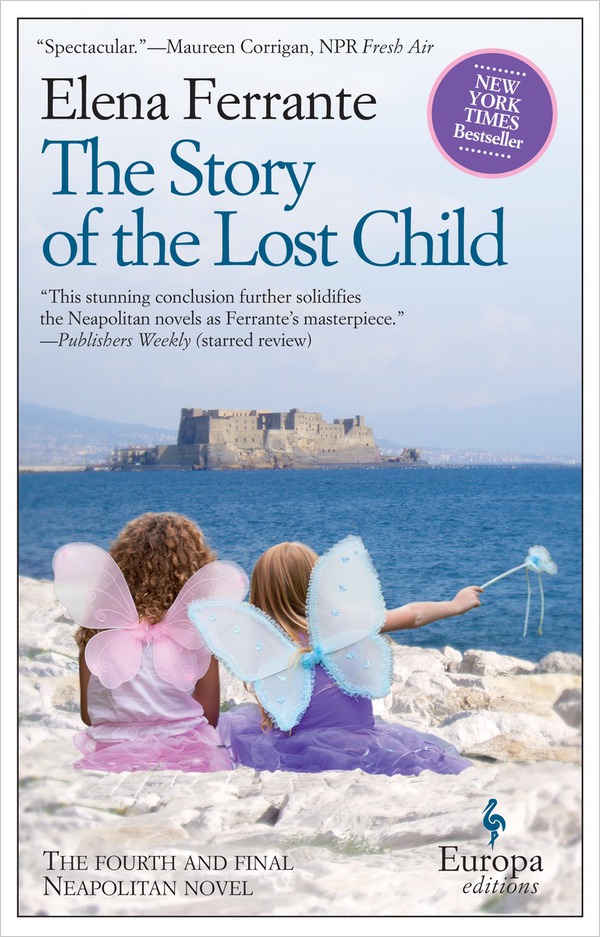

My Brilliant Friend

Wednesday, July 11, 2018

Math, not people

W asked me to join him and several others on the organizing committee for a research program to take place at a mathematics institute. The pre-proposal, which W and another organizer had already written, was due in a couple of days. My guess is that I was added to the committee at the last minute as its "token woman".

Thursday, July 5, 2018

"You must be mistaken!"

When I told American colleagues about a certain result, and mentioned that I had proved (and published) it, the knee-jerk reaction was "Oh, that's obvious." I grew accustomed to that response.

Friday, June 29, 2018

"Foreigners are golden"

Saturday, June 23, 2018

Photocopying exams

This blog post is part of a series designed to give some of the backstory for an upcoming post.

Saturday, June 16, 2018

"Alice, Professor X is here in my office."

Sunday, June 10, 2018

A test of character

Saturday, June 2, 2018

Examples of small groups

W, an undergraduate math major, was having trouble in the algebra course she was taking. In desperation she asked a professor she knew, Robert Gunning, what she should do. He told her to contact me, because I was an algebraist. Plenty of male grad students were algebraists; I don't think it was a coincidence that Gunning sent her to one of the few female grad students. W was the only female student in the algebra class.

Saturday, May 26, 2018

"Name one!"

Friday, May 18, 2018

Stage whisper

Professor Q was supporting candidate Y and I was supporting candidate X, for a postdoc position.

- Almost all the candidates I had supported since I arrived at Ohio State were male.

- All of the candidates he had ever supported were male.

- No one accused him of only supporting his candidates because they were male.

Monday, April 16, 2018

"I'd be happy to hire her if she were male."

Saturday, March 31, 2018

"Don't tell anyone you have this!"

The following post is reminiscent of the January 15, 2018 post.

Sunday, March 25, 2018

J. SMITH and Miss Jane DOE

Tuesday, March 20, 2018

Three Reasons

- The first is that you're a woman. The other students are reserved Englishmen who are shy about speaking to women, so they won't speak to you.

- The second reason is that you're American. They're not accustomed to speaking to foreigners, so they won't speak to you.

- And the third reason is that they don't speak to anyone. So they certainly won't speak to you.

Saturday, March 10, 2018

Math Hookers in the House of Ill Repute

Sunday, February 25, 2018

"They don't have a history of sending students to Princeton"

Saturday, February 17, 2018

They knew the law and obeyed it

Sunday, February 11, 2018

A quick way to reject a paper

Saturday, February 3, 2018

The rules of the game

Monday, January 29, 2018

How do I know how good it is, if I don't know who wrote it?

Tuesday, January 23, 2018

"HIRE ME!"

Dr. Silverberg:The Hiring Committee has met and made its decision. It is not good for you. We will not be making an offer to you.

Dear T,Although I haven't been asked for feedback on my job interview, I thought it might be useful to give feedback on one aspect.Much of my interview with the hiring committee consisted of discussing the question of how to hire more women. In retrospect, my feelings about having been asked that question, and then been rejected for the position, are negative. By the way, I gave standard, well-known answers to that question, but was left with the impression that some of the committee reacted to my response defensively and negatively.I hope that this feedback is helpful for your future job searches.Best regards,Alice