Over the years, I've told colleagues and friends about things I have seen or experienced. Many times, people have said that I should write them down so that they won't be lost and forgotten, since some of them might be useful parts of our history. I've been writing them down, without being sure what I would do with them. I decided to gradually post them on this website, and see what reactions I get. I suggest reading from the bottom up (starting with the August 2017 post "The Meritocracy"). Thoughtful and kind feedback would be useful for me, and would help me to revise the exposition to make it as useful as possible. I hope that while you read my stories you will ask yourself "What can I learn from this?" I'm particularly interested in knowing what you see as the point of the story, or what you take away from it. Please send feedback to asilverb@gmail.com. Thanks for taking the time to read and hopefully reflect on them!

I often run the stories past the people I mention, even when they are anonymized, to get their feedback and give them a chance to correct the record or ask for changes. When they tell me they're happy to be named, I sometimes do so. When I give letters as pseudonyms, there is no correlation between those letters and the names of the real people.

Tuesday, July 31, 2018

postscript to July 25 post

Wednesday, July 25, 2018

A mountain of unwashed coffee cups

I visited a mathematics research institute in Bonn, Germany sometime in the 1990s. In addition to offices, each floor had a small kitchen with ceramic coffee cups, coffee-making equipment, and a prominent sign stating that everyone was responsible for washing their cups after use. So I was surprised to find a mountain of unwashed coffee cups piled in the sink.

Wednesday, July 18, 2018

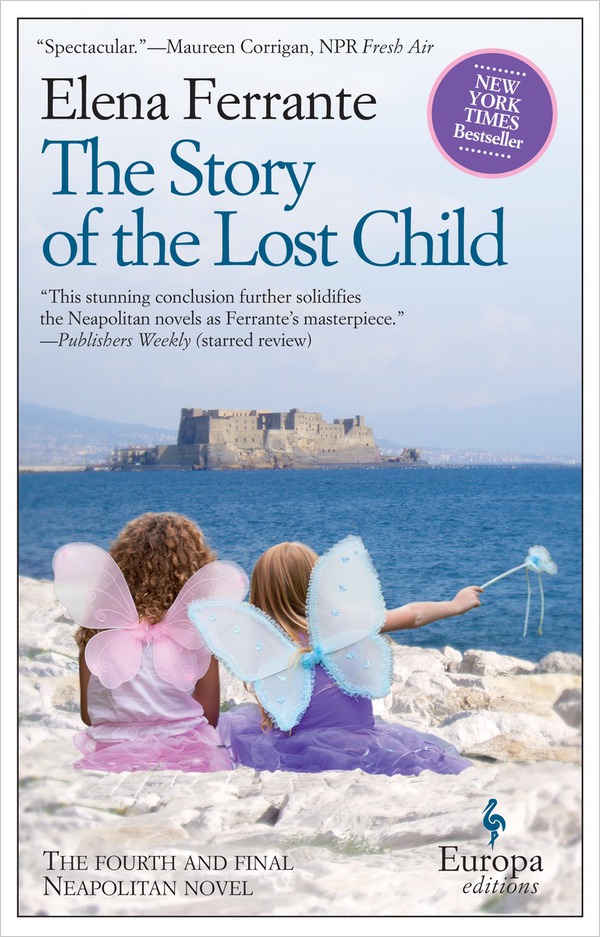

My Brilliant Friend

Wednesday, July 11, 2018

Math, not people

W asked me to join him and several others on the organizing committee for a research program to take place at a mathematics institute. The pre-proposal, which W and another organizer had already written, was due in a couple of days. My guess is that I was added to the committee at the last minute as its "token woman".

Thursday, July 5, 2018

"You must be mistaken!"

When I told American colleagues about a certain result, and mentioned that I had proved (and published) it, the knee-jerk reaction was "Oh, that's obvious." I grew accustomed to that response.